Episode 4, Arendt, Jonas and the ethics of technology

06/07/2021 by Preligens

To listen to this episode :

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Deezer

Other

INTRO

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) and Hans Jonas (1903-1993) - were two eminent intellectuals of the 20th century, two Jews, two Germans driven into exile by Hitler's rise to power in 1933; friends, lovers for a few days in their early youth, but above all one of the most fruitful philosophical dialogues in history.

On scientific issues, Arendt confessed her fears of a decline in thought and morality in the face of the power of new techniques; Jonas understood her doubts and succeeded in modelling a new ethics of tech practices in a book that was to become a landmark at the end of the 1970s - "The Imperative of Responsibility". Let's try to get to the bottom of this duo with Leslie Westfall, in charge of partnerships and alliances at Preligens.

Friends through tragedy

Hans Jonas describes the young Hannah Arendt with emotion at her eulogy in 1975: "... shy and reserved, with astonishingly beautiful features and lonely eyes, she appeared at once as someone exceptional, unique... there was an intensity, an inner direction, a way of getting to the bottom of things that spread a magical aura around her. She possessed an absolute determination to be herself," he continues, "a tenacious will that was matched only by her great vulnerability..."

It is difficult not to understand this vulnerability: the Nazis came to power in the early 1930s - persecution of opponents and minorities began systematically - and Hannah and Hans immediately understood that they had to flee their own country before their own lives were threatened.

Hannah went to Paris where she organised Zionist associations before emigrating to the East Coast of the United States after the French invasion of June 1940. Hans, on the other hand, went to London and then to Palestine before joining the fight on the Italian and German fronts during the war. Afterwards, he taught in Canada and finally made his way to his final destination: New York. It is in this city that the two friends were reunited - alive - and now found themselves unable to separate their profession of philosopher from contemporary realities. Through their humanist lens , they tried to understand the last world war - the historical chronology that led to it, the murderous ideologies that animated it and the relationship of its key actors to innovation.

Image 1: Hannah Arendt in 1933 - the beginning of exile at 27

Hannah's worry

Hannah Arendt is not one of those intellectuals who are nostalgic about the pre-scientific era - the ones who long for those simpler, purer times, when the human species did not yet dominate nature. If her imagination frequently brings her to Greece or ancient Rome, to think alongside Plato, Socrates or Saint Augustine, she is not against the principle of scientific progress. However, scientists themselves have disappointed her throughout her life. Nazi and communist ideologies have made them accomplices to countless atrocities in her opinion. This is how she talks about it in "The Origins of Totalitarianism", I now quote her: "the persuasive power of these [racial or class] ideologies took hold of the scientists who, ceasing to be interested in the results of their research, left their laboratories to preach their new interpretations of life and the world to the masses..."

Therefore, she is not convinced when, after the war, American entrepreneurs tell her all about automating tasks with "intelligent brains" as she calls them (we would now say “Artificial Intelligence”). I quote her again: "There are scholars who claim that computers can do what a human brain cannot understand, and this is an entirely alarming proposition; for understanding is really a function of the mind, but never the automatic result of intelligence..." What worries her is the loss of momentum of Humanities and political sciences especially in the face of rapid technical change; with the immediate risk that today's inventors will no longer care about "beauty, measure and harmony" as their predecessors did for centuries.

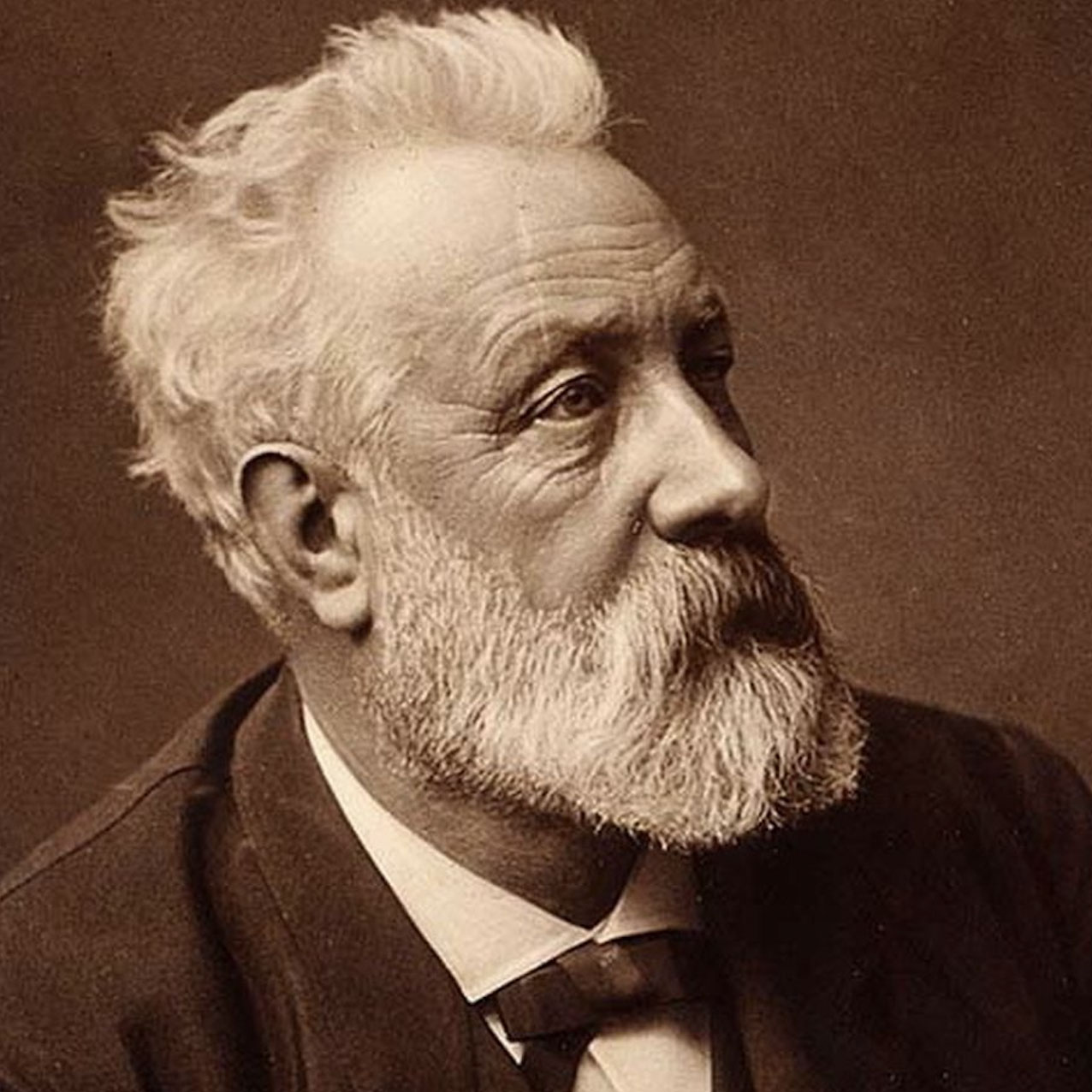

Image 2: Hans Jonas, a 23-year-old student in the troubled Germany of 1926

Hans' answer

Hans Jonas knows where his old friend is coming from. He has read the same authors; he has experienced the same dramas. In his book "The Imperative of Responsibility" (1979) which made him famous, he agrees that- I quote him - "technology today tends to have its own will, its own dynamics".

But above all, he notes that the word “ethics” no longer has the meaning of the ancient centuries to which Hannah Arendt is accustomed. Before the modern times we were in an ethics of honor and respect, where behavior was classified into two simple categories - vice or virtue, good or evil. But the power of human inventions now leads us to favour an ethics of effects - the effects of our actions in space (on the environment) and the effects of our actions in time (on future generations).

From this point of view, digital technologies are just the latest of these innovations that can lead the world down the wrong path, or towards a brighter future, according to him.. Here too, Jonas separates himself from Arendt, in the sense that his book is a real practical manual for "making responsibility possible again", by empowering this new ethic that seeks to anticipate effects before any action is taken. Genetic manipulation, energy resources, protection of nature - all of these innovations are studied meticulously in order to provide a useful moral opinion, an opinion based on real use cases.

The end of his great book, published a few years after Hannah Arendt's death, is like a call to the afterlife: Hans tells Hannah to beware of a permanent scepticism inherited from the Shoah. He is convinced that there is no contradiction and no fatality in man's prosperity at the expense of his humanity. But he is certainly trying to reconnect with his beautiful and brilliant friend one last time when he pleads with humanity to be more humble, to show respect for the planet. His last words attest to this: "Respect alone will remind us of the limits we must not reach, and protect us from the temptation to violate the present at the expense of the future".