Episode 2, Stanley Kubrick and the relationship man-machine

Intro

It is often said that Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) is the filmmaker of all genres - horror (with "The Shining"), war (with "Full Metal Jacket" or "Paths of Glory"), historical drama (with "Barry Lyndon"), relationship troubles (who can forget "Eyes Wide Shut"?..). Certain themes recur frequently in his filmography; and among them, the notion of human will is of particular interest to Michael Benhamou, director of public affairs at Preligens.

Controlling for human irrationality

If it is rare to come away from a Kubrick story with joy, it is just as common to emerge grown from it, motivated even. The filmmaker polishes his talent in the victorious New York of the post-World War II years, whose breath will carry through to the optimism of the 1960s, moon conquest and Woodstock included. From that sequence, our author will draw a taste for the latest technologies, the latest computers, the latest cameras. It is even said that he was fascinated by an IBM innovation that allowed him to type a keyword so he could find his own ideas among several thousand notes (1).

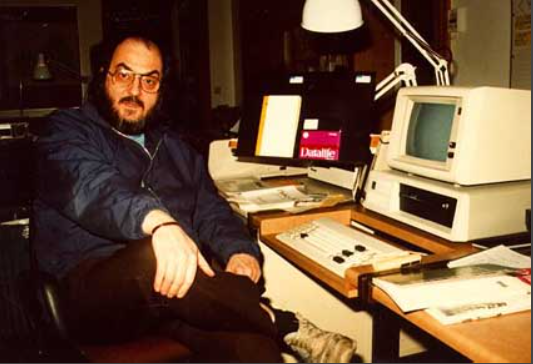

Figure 1 Kubrick in his Childwickbury home (UK) http://kubrickonia.blogspot.com

But his generation's “joie de vivre” is tempered by a longer-term reflection on the weaknesses of human nature. Between the immense capabilities for discovery allowed by our brains on the one hand and the unpredictability of our emotions on the other, how can this species’ value be truly measured up? What chance does it have of ensuring its own survival on Earth and of rising even higher in the universe?

That is precisely why he spent years studying the life of Napoleon Bonaparte – an obsession he never managed to convert into a script. Napoleon, the conquering and brilliant Frenchman who, in his opinion, lost everything through jealousy and impetuosity(2). Kubrick tries to depict similar patterns in his film "Doctor Strangelove" released in 1964. At this juncture of the Cold War, when strategists like Herman Kahn wrote(3) that American deterrence made the mathematical probability of an atomic war "almost negligible", Kubrick wants to remind us that we must never forget to include human error or temporary madness as factors in this type of calculation. His film was to have a considerable impact on nuclear safety measures henceforward.

Reversing roles between humans and machines in 2001

In "2001: A Space Odyssey", released in 1968, the American filmmaker imagines a reversal of roles; he wants to see if machines are better than these homo sapiens who are decidedly too uncontrollable. His human characters are neutralized, cold, turned off; and at every turn, it is the humor and liveliness of the robot HAL, endowed with Artificial Intelligence (AI), that brings cheerfulness back to the crew of his spaceship.

Except that HAL is the sole master on board, the sole pilot, and the only one who knows the real objective of the mission – reaching planet Jupiter to discover the first traces of extraterrestrial life. Since the mission’s strategic command prefers to entrust this information to the machine rather than to the humans in order to avoid leaks and emotional outbursts, the weight of this responsibility slowly becomes the source of a "programming conflict" within the computer; for it is asked to tell the truth to the humans who are accompanying it, in its capacity as operator of the expedition, while at the same time HAL is required to hide the historical goal of the trip from them... a schizophrenic coding of sorts.

HAL panics, loses self-control like Napoleon before throwing himself into the Russian winter before a digital homicide attempt begins... but to avoid spoilers and to see if the cosmonauts manage to save their lives, I strongly advise you to see this masterpiece if you have not already done so.

Figure 2 On the set of “2001: A Space Odyssey” © UAL ARCHIVES

Pragmatic, not pessimistic

So is Kubrick a new tech pessimist?

To understand his true state of mind, an interview given to Playboy at the time of the film's release allows us to go further. Kubrick believed, and I quote, " that our relationship with machines will become ever more complex as it becomes more intelligent. Eventually, we will have to share our planet with machines whose intelligence and capabilities will exceed our own. But our relationship, if well managed by humans, could be extremely rewarding for society..."; moreover, he says humanity is not doomed to become (I quote again) "a race of dehumanized zombies plugged into simulators while machines do our work and our bodies and minds atrophy.(5)"

More pragmatic than pessimistic, then. His film in fact makes us aware of the risk for man to renounce his will by sinking into digital comfort. And decades after this film, for all those who today develop solutions based on Artificial Intelligence and want to think about their ethics, his warning reminds us of a conceptual precaution: to preserve the place of man in the decision-making process and the evaluation of the technologies produced.

To sum it up, Stanley Kubrick is telling us that the human species is not perfect (even Napoleon had faults they say..), but it is mankind that gives meaning to the world through its discoveries; the same mankind that gets this planet closer to the stars and that must now assume its responsibilities.

Literature

1) Alison Castle, « Stanley Kubrick’s AI », in The Stanley Kubrick Archives, Alison Castle (dir.), (Köln, London, [etc.], Taschen, 2005), pp. 119-122.

2) Alison Castle, Kubrick’s Napoleon, the greatest movie never made, Taschen, 2017

3) Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War, Princeton University Press, 1960

4) Aurélien Portelli, Sébastien Travadel, Franck Guarnieri, « Quand l’IA tue : 2001, l’Odyssée de l’espace ou le récit de la fin de l’espèce ? », La Recherche, 2018

5) Eric Norden, « Stanley Kubrick : Playboy Interview », Playboy, 1968